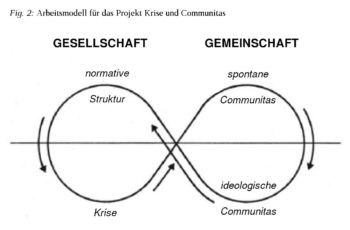

Communitas is a form of community. In contrast to the conventional, often romanticised “community”, communitas is not understood as a container featuring an inside and an outside. Instead of excluding “the other”, it embraces otherness and multitude. Communitas is an open relation to the other, the interrelationship between entities without hierarchy, without defined position within the structures of power.

Communitas subverts and annihilates existing inequalities and focuses solely on the being-in-common, but without wanting to uniform diversity. Communitas is conceptually connected to the “political” interrupting and subverting the present order. It opens up as a dissonance of perception, an interval of the unpredictable. The “political” is the place where social movement can happen, and therefore it is the place of communitas – beyond structures and hence always precarious and fleeting.

Considering concepts of communitas, however, we encounter some issues.

One difficulty is the balancing act between the common (collective) and the “own”. Roberto Esposito mentions this as he discusses the semantic core munus of the Latin word communitas. Munus accentuates the service to the common and thus pushes towards the abandoning of the personal. Communitas therefore is sometimes understood as endangering individual existence, identity and freedom – the self drowning in the common.

The dismissal of hierarchies from the idea of communitas also bears problematic potential. To concentrate theoretically on unstructured, open, and egalitarian relations may lead to the whitewashing of existing inequalities in favour of an ecstatic equality – which de facto does not exist. One might suspect that the prevalence of white male western academics among the theoreticians of communitas is not fully coincidental: their privileged position prevents the experience of discriminatory structures, leading to a conceptual neglect of inequalities that do not touch them directly.

A similar thrust shows the criticism of the conceptualisation of communitas as “coming.” As long as communitas will be constructed solely into a fleeting future, its political impetus will be ephemeral, too. Can communitas be set into present and “vulgarised” in order to gain political force? How can we fruitfully deal with existing inequalities but still work towards the political utopia of communitas?

[ Also, regarding the field of cultural studies, we could ask: how can we explore communitas in cultural practices, if it cannot exist? ]

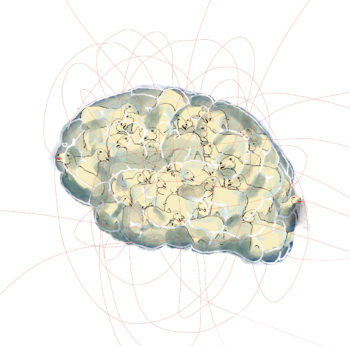

Focusing on relations instead of a “container” leads to the question between whom relations exist or may be installed. There is first a terminological issue, whether we should speak of subjects, individuals, or even persons. Considering the core munus, the sharing of the common, it seems questionable to speak of individuals: in what way is an individual un-shareable (indivisible) if it solely consists of its con-dividuality? Do we need to assume singularities, whose only trait is to exist in common with others? At the same time, we might want to ask whether communitas extends only to human singularities – an idea not explicitly spelled out, but secretly underlying concepts of communitas. Which role do we appoint to the idea of self-responsible, conscious agency in times of anti-speciesist movements and posthuman cyber-technological developments?

Readings:

Joseph Vogl, ‘Einleitung’. In Gemeinschaften. Positionen Zu Einer Philosophie Des Politischen, edited by Joseph Vogl. Frankfurt a.M.: Suhrkamp, 1994. 7–27.

Roberto Esposito. Communitas: The Origin and Destiny of Community. Stanford, Calif: Stanford University Press, 2010.

André Lepecki, ‘From Partaking to Initiating: Leadingfollowing as Dance’s (a-Personal) Political Singularity’. In Dance, Politics & Co-Immunity, edited by Stefan Hölscher and Gerald Siegmund. Zürich: Diaphanes, 2013. 21–38.

Gerald Raunig, ‘After Community: Condividuality’. In Dance, Politics & Co-Immunity, edited by Gerald Siegmund and Stefan Hölscher. Zürich: Diaphanes, 2013. 271–279.