‘Seek unto them that have familiar spirits, and unto wizards that peep, and that mutter: should not a people seek unto their God? for the living to the dead? To the law and to the testimony (…).’[1] This passage from the book of Isaiah (8:19–20) is one of the thirteen Old Testament indications of the existence of the practice of calling up the spirits of the dead – necromancy – in the ancient Jewish state.[2] Necromancy (Gr. νεκρομαντεία) is not the same concept as the cult of the dead, or ancestor worship[3], as it is not primarily about honouring the dead through a series of (funerary, mourning) rituals or veneration of their memory within a specific community (society, the local community, or the family). This particular magical practice, which means literally ‘prediction of the future, divination with the help of the dead’, is aimed at obtaining from the deceased information about the unknown causes of certain occurrences or the future course of events with a view to changing the fate of those affected by a crisis. Necromancy does not, however, necessarily involve ‘encounters with the souls of the departed during the spirit journeys of shamans, apparitions of ghosts, or communications in dreams.’[4] What is important is the visibility of the dead, who usually appear through a medium, a kind of shaman who sheds his or her own identity for the duration of the practice in order to become one with the dead person being called forth.

Due to its strong connections with witchcraft and divination, necromancy has been considered a suspicious, or even blasphemous, activity in the Judeo-Christian tradition since its beginnings. In the Old Testament book of Leviticus (19:26, 31) the injunction against this ‘impure’ practice is stipulated next to the prescription of kosherness: ‘Ye shall not eat [any thing] with the blood: neither shall ye use enchantment, nor observe times. (…) Regard not them that have familiar spirits, neither seek after wizards, to be defiled by them.’[5] In the Middle Ages the Catholic Church considered necromancy, or any involvement with sorcery, a manifestation of ‘black magic’. This led not only to the proclamation of such practices heretical, but also to a common confusion of related words, and at the same time a mocking depreciation of the term necromantia (from Greek nekros, dead) into nigromantia (from Latin niger, black).[6] This process, so characteristic of Western culture, consisting in identifying what is black or dark with evil or demonic qualities, found its subversive form of expression in ‘black books’ (libri nigri) or ‘the art of black [magic]’ (ars atra). As a result, necromancy survived on the fringe of Western culture: in grimoires written between the Middle Ages and the 18th century, in alchemy and Kabbalah[7], in occultism, and also in certain manifestations of contemporary popular culture, for which the question of ‘the undead’ has become a major issue. [8]

Necropolitics

Questions about the boundary between the worlds of the living and the dead, about the possibility of overcoming death as something final, and the potentiality of communicating with the departed have also been salient characteristics of modern art. Perhaps the most conspicuous artistic expression of interest in the evocations and returns of the dead into the world of the living in Polish culture was Mickiewicz’s Forefathers’ Eve, which made a lasting imprint on subsequent generations of artists, especially those on the fringes of official culture, such as Tadeusz Kantor or Jerzy Grotowski.[9] Primarily at moments of major, insurmountable crises of culture in the 20th century, caused by civilizational catastrophes in the form of the two world wars, the issue of the ubiquity of death in the reality of the living returned repeatedly with considerable force of impact, though in a form different from that which it assumed in the 19th century. A characteristic of 20th-century (neo)avant-garde art was an obsessive interest in radical experiences of the body, which was manifested in both ‘theatres of war’ in a penchant for representing fragments of the human body and organic remains.

The presence of a dead body among ruins and charred remnants was not only indicative of its detrital nature but also highlighted the tangibility of war, exposing its necropolitical dimension. The body was indeed that area where the boundary between life (bios) and death (nekros) proved particularly fragile under the circumstances of a state of exception. Although the compulsive revisiting of mutilated bodies was an obsession of surviving artists after both world wars, representations of the human body as a site of death management definitely differed between the two post-war periods, not only due to the unprecedented use of mass technologies in the Second World War to murder millions of human beings, including six million Jews, in the name of the racism-based Nazi ideology. The Great War had brought independence and statehood to Poland, which to some extent obscured the necropolitical nature of wartime violence in Polish culture at the time.[10] The Second World War, for its part, branded the postwar visual and performative spheres with its ruthless cruelty, projecting criminality as a permanent condition of the dehumanized modern culture.

It is impossible to experience war without living through one; however, by means of art, theatre, film and literature it is possible to imagine the postwar landscape. Poverty, hunger, disease, bodies of dead children, bodies of raped women and crippled men, burnt-down cities, moral depravation, severed family and social ties – these components of ‘the great fear’[11] culminated in permanent dread of another war breaking out. The obsession with the menace of war as an insurmountable crisis of culture – in which not only the positions of the perpetrator and the victim became unclear but also the difference between a human being and a remnant of one became blurred – came to the fore in the work of many artists, among them Tadeusz Borowski, Władysław Strzemiński, Tadeusz Kantor, or Andrzej Wróblewski. On a postcard he sent in 1949 to Witold Damasiewicz, Wróblewski jotted down the following cultural ‘model’ based on the presumption of a singular situation without a way out:

I. The Second World War…

- The war humiliates man – conspiration, questioning, imprisonment

- It ruins societies – forced labour, camps

- It destroys the nation – executions, bombings, demoralization

II. We’re still threatened by war…[12]

In the same note he also elaborates on the theme of danger, pointing to one main cause of the cyclical upsurges of ruthless violence in the 20th century: racism. Notably, he does not associate racism solely with the state ideology adopted by the Third Reich but perceives it in various systems of lawlessness, cruelty and exploitation overlapping in many parts of the world (and all the more terrifying for it!). One needs to be aware that Wróblewski wrote these words in the context of the antisemitism that was still present in Poland at the time and accompanied the debates on the Holocaust and the forms of its commemoration, and also after the atomic attacks on Hiroshima and Nagasaki; this was also the time of Indonesia’s struggle for independence, and the revolution in Algeria had just been nipped in the bud, and the tensions foreshadowing the war in Korea were running high. Given that the time of the German occupation was marked by the extermination of the Jews, the next war, the artist seems to be arguing, could lead to a Holocaust of other discriminated ethnic groups: ‘1. Imperialism enslaves nations – freedom fights in Greece, China, terror / 2. Persecutes coloured people – persecution of the Blacks, of colonial nations.’[13] In his ‘Commentary on the Exhibition of Modern Art’ Wróblewski not only formulates a similar thought but also uses it to argue for the inseparable co-presence of living and dead bodies in his own paintings: ‘(…) we want you to be aware of war and imperialism, about the atomic bomb in the hands of evil people. We paint pictures that are as nasty as the smell of a corpse. We also paint pictures that make you feel the closeness of death’.[14]

How comprehensive his famous 1949 Executions appear from this perspective (that of also involving the viewer in recurrent violence!): paintings evolving from depictions of the experience of death and the precariousness of human existence into a kind of knowingly instituted communication between the living and the dead. In this series, whose repetitiveness somehow conveys the serial nature of death, Wróblewski undoubtedly identifies the management of death (and necro- rather than biopolitics) as the essence of war. Nevertheless, as rightly pointed out by Noit Banai, the artist ‘performs a moral obligation to confront the necropolitical erasure of a racialised population from the national public body at the same time as he anticipates a Socialist society that has not yet been normatised or betrayed.’[15] This may be why Wróblewski succumbed so easily to the optimistic version of postwar internationalist Communism, which was manifested, among other things, by his official participation in the 3rd World Festival of Youth and Students in East Berlin in August 1951. It was in connection with this event that the Executive Committee of the World Federation of Democratic Youth formulated an address that was ideologically compatible with Wróblewski’s stance. We read in this document: ‘All humans and the whole cultural heritage of humankind are in mortal danger. But war is not inevitable. The nations of the world are strong enough to defend the peace and keep a tight hand on those seeking to cripple our lives, shatter our dream and deprive us of the future.’[16]

It might, therefore, be said that the postwar period in Poland was characterized by a singular dialectic of death and rebirth, which generated in the shattered society and the degraded humanity strong need to replenish their spiritual and material losses and at the same time a desire to create a new social utopia without obliterating the time of the war as a space of trauma. The works of Andrzej Wróblewski, but also of the other heroes of this exhibition – Andrzej Wajda and Alina Szapocznikow – became (albeit to varying degrees) expressions of this ineluctable aporia. Ubiquitous in their works, the coexistence of life and death, not only as areas constituting immanent features of the ‘landscape after the battle’ but also as an indispensable precondition for altering a preordained fate, makes it possible to perceive their art as a kind of necromantic practice, conjuring up the dead in order to overcome a crisis in the world of the living. For their art was made after the war, from a position which Andrzej, in the cult scene involving vodka glasses in Wajda’s Ashes and Diamonds, describes with the ambiguous statement: ‘We’re alive!’

Scenic Bios and Performative Nekros

Wróblewski’s paintings cannot be perceived solely as documentation of the horrors of war, its methods of manufacturing death, and the liquidation of human lives, and thus as a visual representation of necropolitics. The artist’s conceptualization of the body as a political entity which is the key stake in the war politics of death was accompanied by a search for new forms of representation of the body in the context of the idea of ‘direct realism’ that he sought to formulate. To evoke a sense of the proximity of death in the viewer, and thus to attain a certain effect of reality during the viewing of his Executions, Wróblewski developed a singular technique, by exercising the body in a variety of situations, such as ‘a discus thrower in mid exertion’, ‘a dancer in the thralls of a jitterbug’, or ‘a woman smoking a cigarette’, as cited by Noit Banai.[17] The purpose of those exercises, however, was not to depict commonplace, everyday activities[18] but rather to work on activities that are governed by certain recurrent rules and are recognizable for no other reason than the fact that they violate the ordinary, everyday balance of the body. Alina Szapocznikow’s technical exercises, such as the studies Cripple or Felled, were of a similar nature, giving rise to the development of the idea of sculpture as a space of confrontation between organic and inorganic matter, so characteristic of this artist.

From the perspective of anthropology of theatre, this type of ‘extra-daily body techniques’[19] provides the basis for generating the ‘surplus’ energy required to employ ‘incoherent coherence’ to transfer the bodily tension onto the spectator. It is only through a body technique that the scenic bios of the actress/actor on stage can prove sufficiently determined to transcend the framework of the production and evoke the desired effects in the spectator. And I think similarly Wróblewski in his sketches must have developed such a way of representing the body that could take complete control of the intellect and emotions of the viewer. As a result, in his staged executions death is not a state but – all the more cruel for it – a process, a passage from living to dead. Subjected to a kind of training in social situations, the body, i.e. the living body exercised by Wróblewski, was thus the starting point for the representation of dead bodies aiming to shock the viewer: fragmented corpses and mutilated beings confronted with one another at various stages of dying. This singular artistic process, responsible for generating tension between the living and the dead in Wróblewski’s Executions, can be described as a transformation of the scenic bios – the body technique developed by the artist – into a performative nekros – a force of affective impact, a kind of causative capacity in the work of art as an autonomous object.

‘I’ve seen those paintings. So cruel…,’ is how the posthumous exhibition of Andrzej Wróblewski’s work is commented on by Beata, the wife of ‘the Director’, one of the protagonists of Andrzej Wajda’s film Everything for Sale and at the same time the alter ego of the director himself. Wajda was not only Wróblewski’s friend but also, from the start of his studies at the Academy of Fine Arts, a great admirer of his paintings. It was his works that were actually the reason why Wajda decided against the career of a painter. It may have been his fascination with Wróblewski’s ability to represent the body in motion and produce the effect of the processuality of dying that compelled Wajda to choose film, as a medium whose essence is moving images, i.e. making something dead come alive. Everything for Sale (possibly the most niche film of this otherwise mainstream director) seems a singular attempt to problematize the relationship between the painter and the filmmaker in the form of meta-reflection on art as a space of confrontation with death. While the most conspicuous level here is the theme of the director’s loss of his actor, occasioned by the tragic accident of Zbyszek Cybulski, the deep meaning of the film is far from anecdotal. Because an obsession with death is present in nearly every scene of this film, causing a kind of reversal in Wajda’s previous explorations, where his artistic urges were oriented towards creating new forms and projecting possible worlds rather than towards compulsive recreation or reenactment of past events.

It is in this autothematic film by Wajda, made soon after the events of March 1968 but without any open political references, that the theme of death manifests itself with greatest intensity as an insurmountable compulsion to repeat. This starts with the sequence in which Beata’s head, placed between the two halves of a table top pulled apart, brings to mind a guillotine mechanism; continues with the train accident scene, which is reenacted several times, the crime scene staged (faked) by policemen planting a dummy, which Andrzej, the Director, later ‘kills’ again by running it over with his car, and the mediumistic scene of evoking ‘Warsaw ghosts’, and is crowned by the shocking sequence with the merry-go-round. This last scene, which symbolizes the apathy and passivity of the apolitical elite, is not only an overt reference to actual events during the uprising in the Warsaw ghetto, as described by Jan Błoński in his famous essay ‘The Poor Poles Look at the Ghetto’, but also an expression of the fundamental problem of Polish responsibility for the Holocaust of the Jews: the merry-go-round scene is also Wajda’s autothematic return to his 1954 film A Generation and at the same time a prefiguration of Holy Week, made in 1995, i.e. the productions in which the director made renewed – though ideologically insufficiently conclusive – attempts to deal with the subject of Polish-Jewish relations. The peculiar depoliticization of the ‘merry-go-round situation’ recurring in these three films shifts the focus every time from potential reflection on the invisibility of the Holocaust to the very act of looking on, staged by the film director.

Wajda’s main point of interest in Everything for Sale is – as in the work of Wróblewski and Szapocznikow – the (absent) dead body of a human being. The reflection on the fragility or precariousness of life is not, however, conditioned here by either recognition of the body as an active subject/passive object of necropolitics (Wróblewski) or deep personal experiences of life in a camp (Szapocznikow). The body in Wajda’s film becomes a key medium primarily due to the selection of reenactment as an artistic strategy whose essence is belief in the possibility of living access to history through the body and generating reality through performative – embodied – repetition. In this outrage of repetition, the body becomes living proof of the death of the departed, a testimony in flesh which gains its seal of legitimacy in the experience of the living and not in historical truth. The obsession with recreating events, so characteristic of Wajda’s film, thus shows reenactment as an artistic practice which seeks in the living body a testimony to the death of an Other. After all, reenactment is nothing other than a repeated event which leaves behind ‘residue’ that forms a sediment in the body, entangled as of that moment ‘in a network of body-to-body transmission of affect and enactment’.[20] The bodies of the actors in Everything for Sale – complete with their so diverse scenic bios! – are transformed in the successive reenactments of past events into living relics of history, a kind of affective residue – into a performative nekros. This is how the necroperformative nature of reenactment becomes manifest in Wajda’s film, because what dead residue does to the living is equally important as the communication of the living with the dead.

The Death of the Author

The exceptional status of Everything for Sale compared to the other historical, political, or even persuasive films by Wajda is occasioned by its radical autothematism, which makes it possible to engage in reflection on film art as a necromantic practice. Despite the seemingly strong presence of the auteur in Everything for Sale (Wajda autobiographically camouflaged as Andrzej, the ‘Director’ character, played by Andrzej Łapicki, with his wife Beata, played by Beata Tyszkiewicz, who appears in the film with her daughter Karolina; Wajda as a director who has lost ‘his’ actor – Zbyszek Cybulski – and finds a successor to replace him in this film – Daniel Olbrychski; Wajda as Wróblewski’s friend who, disappointed by the fact that this great genius of painting has still not gained international fame, arranges a repeated posthumous exhibition for him in the film), as the ultimate authority in control of the narration, and at the same time as a key figure of modernity (also deeply ingrained in the capitalist order), he is put to death.

Due to the use of reenactment as an artistic strategy, based on repetition and therefore without a source in the traditional meaning of the term, in Wajda’s film we have a situation where the author (director) becomes a kind of shaman ‘whose “performance” – the mastery of the narrative code – may possibly be admired but never his “genius”,’ in the words of Roland Barthes.[21] In his famous essay ‘The Death of the Author’ Barthes describes the moment when the author symbolically detaches himself from the work in order to create a situation where ‘the voice loses its origin, the author enters into his own death, writing begins.’[22] He thus points to the artist not as the one who has knowledge on the interpretation of (his or her own) work but rather as an intermediary in communication between the work and its recipient, because it is the latter who gathers the traces scattered in the field of such communication – the traces of which the work is made up. In the case of Everything for Sale, the viewer, confronted with a series of phantom images and reenactments – embodied evidences of the death of an Other – engages in direct dialogue with the dead outside the mystery of the author, as it were.

Understood in this way, the author’s death, which makes it possible to remove the artist from the work in order to enable the recipient to come into direct contact with the traces that led to the creation of the work, is a category indeed shared by all the protagonists of this exhibition – though in the cases of Wróblewski and Szapocznikow the erasing of the author, while remaining an autothematic gesture, also has an existential dimension. Andrzej Wróblewski, who was obsessive in his depiction of the process of putting an Other to death, was always staging his own death too. The theme of suicide accompanied him from the beginnings of his career: as a thought relating to his excessive exploitation of himself occasioned by the inseparability of life and art, it first surfaced in the notes he made in January 1948: ‘if I’m not considering suicide as my life’s entertainment (…) I must diminish the intensity of my experiences,’[23] and subsequently, more pronouncedly, in his ‘Personal Notes’ from 1955–1956: ‘no living person can bear incessant activity.’[24] Thus, paradoxically, his desire to create a society of the future was coupled with an intention to annihilate himself as an individual.

In the ‘Diary of a Suicide’, a piece of prose he wrote as a marginal activity alongside his painting, Wróblewski admitted to a ‘suicide hydra’ which regenerated within him ‘with an exactness amounting to destiny’ and was responsible for his compulsion to be incessantly designing his own death – under the wheels of a train engine, from shots fired in the street, or by hanging.[25] In ‘Multihorizonality and the “Perspective Incompetence” of Early Naturalism’ he wrote about the processuality of death as if he were reproducing the course of his own thoughts while at the same time trying to come to a closer understanding of his own paintings: ‘A certain observation would help explain the content of a dying man’s consciousness even better. The sequence (1) – (2) (3) [consciousness, death, unconsciousness; D.S.], apart from the gradual discarding of perceptions and memory images by the consciousness, is also characterised by a reduction of the (spatio-temporal) location of experience.’[26]

From this perspective the process of dying as staged in the Executions reveals itself as a prefiguration of his own multiple deaths, especially when one considers that the jacket recurring in this series of paintings, in which Wróblewski repeatedly packaged the bodies of the figures subjected to execution, resembled the artist’s own jacket. ‘The void feels bad / Wind is menacing to me / I might end up finding shelter / in death’[27] – in this four-line poem from 1954 he projected an image of his own real death, which came in the mountains three years later. Wróblewski sealed his own fate, which was marked with his irrevocable need to pursue art as a necromantic practice, with the finality imposed by his inability to forget death as part of human existence. With his premature death he also exposed the danger inherent in continued contact with the dead, thus vindicating the key rule of necromancy: sending the dead back is as important a stage of the ritual as calling them up, otherwise the dead may become a threat to the living.[28]

Reenactment, Staging, Transubstantiation

The issue of the author’s absence is manifested in different ways again in the work of Alina Szapocznikow, to whom – as a female artist working within a patriarchal culture – the status of the postwar artists diagnosed by Wajda as that of ‘the generation of sons’ obliged to reproduce the experiences of their own fathers[29] remained irrelevant. The question of staging oneself in the figure of an Other, so characteristic for Wróblewski, was equally problematic with Szapocznikow, especially when one considers that, as a woman and a Jew, she was an embodiment of a double alienness in Polish culture. With its undercurrent of Catholicism, Polish culture – like any patriarchal culture – developed an irreducible difference between man and woman, refusing to recognize any other than masculine historical continuity, and thus denying the woman subjectivity and the possibility of authorship. As argued by Sandra M. Gilbert and Susan Gubar, in the patriarchal culture ‘the text’s author is a father, a progenitor, a procreator, an aesthetic patriarch whose pen is an instrument of generative power like his penis.’[30] Without a doubt, her recognition of her own difference in relation to the masculine authority of authorship had a strong influence on Szapocznikow’s work, marking her sculptures – from the start – with the ‘anxieties of this difference’[31], because, if we were to regard the chisel as a metaphorical penis, so to speak, then with what organ could a woman generate sculptures?

Perhaps this early recognition of a deficiency (of authorship, of subjectivity) provided the momentum for Szapocznikow’s unique creative process, allowing for the ongoing overlapping, and consequently co-presence, in her works of her experiences relating to the cultural perception of femininity and her existential experiences relating to the extreme memories of her time in the camps. Despite the double stigmatization and disinheritance of history – as a woman and a Jew – sculpting became for Szapocznikow not so much an activity enabling her to articulate her alienation as rather a space for opening up and augmenting artistic freedom, for filling in ‘the holes in discourse, the blanks and gaps and silences’[32] with matter. Paradoxically, neither cultural nor aesthetic limitations were what would haunt Szapocznikow like spectres of suppressed expression. Her work remains material through and through, even indecent in its excessive materiality, while her attempts at self-determination, especially in her series of portraits which display characteristics of self-portraits (Autoportrait, Multiple Portrait, Double Portrait), fall outside the category of identity, arguing that the mystery of the artist’s bodily presence is in the vestiges of (her) body and matter. Through art (the creative process and the aesthetic act), organic remains and dead matter undergo transubstantiation – a repeated metamorphosis into ‘body and blood’. This aesthetic, secular act of transubstantiation causes a singular profanation – of both patriarchal culture and Catholic theology. Perhaps the most pronounced form of expression is given to this transgression in her 1957 sculpture entitled Mary Magdalene, representing the woman sinner with a head shaped like a male organ.

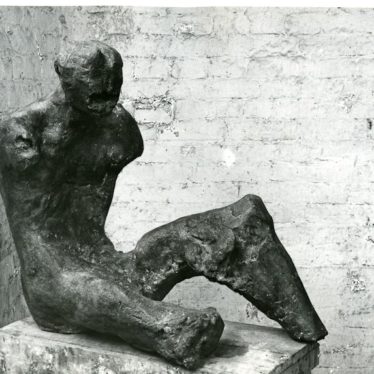

I have a strong feeling that Szapocznikow’s principal idea of the body was forged in those early figural sculptures, directly influenced by the reality of the violence she had experienced during the war and falling within the sphere of impact of her gradually manifesting trauma. This is evidenced by Exhumed from 1955, the artist’s perverse game played with the political and symbolical power of exhumation and identification of victims, which lies ‘at the intersection of different moral, metaphysical, and psychological preoccupations and anxieties concerning mortality, individuality, the fallibility of memory and historical narrative, the infallibility of physical proof, and the possibility of redemption and closure in the wake of trauma.’[33] While it is possible to offer a reading of Szapocznikow’s Exhumed based on identifying the sculpted figure with the Hungarian communist László Rajk, the form of the sculpture wards off such extreme concretization of meanings – both historical and ideological. This is so because the viewer is confronted here with an anonymous, charred fragment of a body, void of any physiological details, in which the manner of its mutilation (arms absent, legs stumped, face lacerated, or possibly just distorted by a grimace of terror?) is clearly indicative of wartime violence as the cause of the total deformation of the body.

Necroperformance

Exhumation – in the case of Alina Szapocznikow’s sculpture – is not so much a political as an artistic act: Szapocznikow retrieves a victim of the war from the grave, as it were, in order to make him or her present among the living again, so that he or she can no longer be ‘silenced, sequestered or denied’.[34] The idea is not, however, merely to protect the victim from oblivion, but also to expose the precariousness of life, show its vulnerability to injury as the essence of human existence.[35] Due to the immanent effacement of the dividing line between living and lifeless, body and objectification, sculpture is a perfect medium for showing the dead body as an outcome of a dual relationship with an Other: as existing ‘in its exposure and proximity to others, to external force, to all that might subjugate and subdue it’, and at the same time as a kind of calling and a ‘condition of responsiveness’ to violence and death. Exposed to others, the body enables ‘a formulation of affect’, and thus ‘a radical act of interpretation in the face of unwilled subjugation.’[36] From this perspective, Exhumed proves to be not merely a commemoration of the victims of violence, or a warning against potential injury to other beings, but also an appeal to the viewer to become part of a community of the living based on an ‘ethics of precarious life’.[37]

Even at the start of her artistic path, her 1955 sculpture Exhumed betrayed a peculiar understanding of the body that would constitute the essence of Alina Szapocznikow’s oeuvre. Her cancer – as well as her earlier wartime and camp experiences – were to expose the body again as the place where the precariousness of the human body manifests itself, and the sculpture as a singular ‘body-archive’ that makes it possible to overcome the crisis of the biological body. The materiality of Szapocznikow’s sculptures – even if it ‘tells’ of a body that is mutilated, fragmentary, vestigial or dead – makes this a lasting body, which, unlike the biological body, is not subject to the disintegration of matter which entails the disintegration of meanings and semiotic structures. The sculptures of Alina Szapocznikow paradoxically enable the sick, the crippled, and the dead to regain the integrity of their bodies, and thus their cultural function is the same as that of burial. This is so because, thanatologically, the corpse must become a body – a representation of the cadaver – and at the same time a sovereign existence, detached from the disintegrating matter, as this is the only way for it to become an active subject. From the perspective of the experience of war victims, especially Holocaust victims whose remains were not identified and did not undergo the funerary rites, Szapocznikow’s sculptures are just such a body-archive, by which their lives are finally lamented in a dignified manner. Her work thus reveals itself to have been a process, many years long, of ritualizing the radically abrupt termination that the Holocaust was.

Wherever a crisis of the biological body manifests, culture develops a ‘body-archive’. The body-archive is a kind of causative material documentation of the past: bones, organic remains, objects, materials, and also remnants of the past undergoing media archivization and technological reproduction, retained in the testimonies of those who lived ‘there and then’ and also in works of art, such as those of Alina Szapocznikow. The ‘body-archive’ stays active, generating tensions between matter and form, artwork and viewer. The shifts of meanings initiated by transformations of matter open up a space for necroperformance – impact exerted by the absent body, mediatized in the material remnants. Archived in works of art, the body calls on another body to act, creating a space where history and memory appear in the process of ongoing negotiation between spirit and matter, between life and death. A necroperformance does not ask after the actual person: here the remnants alone impact the living. This is how Szapocznikow’s sculptures operate – as active material remnants left behind by the absent departed. Her work not so much documents as moves around whatever was unknown or missed in the writing of the histories of the dead.

Andrzej Wróblewski, Andrzej Wajda, and Alina Szapocznikow were artists working in different media and dissimilar aesthetic languages. Nevertheless, their experience of wartime violence, combined with the socio-cultural context and the historico-political circumstances that arose in Poland after the Second World War, made them a community of survivors which assumed the obligation to mediate between the worlds of the living and the dead. Although the war is a kind of irremovable presence about them, their work is not affected by resentment, or ressentiment, which principally involves the inability to forget scenes of violence and the experience of humiliation. Forgoing in their work the idea of being active entities in order to concern themselves instead with intermediation in the communication between life and death, Wróblewski, Wajda, and Szapocznikow strove to turn art objects of ritual power into fetishes permitting the reintegration of the social fabric after the trauma of the war. Their necromantic practices were both a manifestation of their complete loss of trust in religion and an indication that they were looking for solutions which could protect modern man in a radically secular ritual – in art. And then the artists themselves, as special mediators between the world of the living and the world of the dead, as necromancers and shamans, remain in their works – undead.

The text was published in the art catalogue Perspektywa wieku dojrzewania/ Perspective of Adoloscence, ed. Anda Rottenberg, Muzeum Śląskie, 2018.