In this article, I want to explore the ways contemporary art can produce community. By community I mean not a belonging to a specific group, but the concept of communitas as an open, unstructured, and egalitarian interpersonal bonding. The philosophical current circling around this understanding of communitas is closely tied to the Rancièrian concept of the «political» and views art both as a vehicle and incorporation of the political. The political and communitas emerge as and within an ecstatic interruption of the «distribution of the sensible»[1], a rupturing with established hierarchies and an opening up for new possibilities and egalitarian interactions. Therefore, I would like to investigate into the conditions – if there are any – how art can initiate the political and communitas in the sense of an utopian project. This question I will consider at the example of an exhibition called Producing Futures – An Exhibition on Post-Cyber-Feminisms shown in early 2019 in Migros Museum für Gegenwartskunst (Migros Museum for Contemporary Art) in Zurich, Switzerland. It seems important to me to reflect how the political utopias of (post-cyber-) feminist visions as present in an exhibition on contemporary art can inspire movement going beyond the contemplation of the observer. I want to ask about immunitarian/communitarian processes happening during the visit of the exhibition and to find out if the feminist perspective can reframe the understanding of communitas.

How is art connected to communitas, a specific understanding of community conceptualised as an open, egalitarian commonality residing in the political? The line of political-aesthetic philosophy influenced by Jacques Rancière sees art as the field where the political emerges. Both art and the political de-normalise sensual perception. The political emanates in artistic practices from the rifts in the fabric of the sensual order, where the subordinated, abjected, voiceless comes into being. The political hence is a reversal of the conservative, repressive system of norms; it opens up structures and signifies movement. Concepts of such community as presented by Jean-Luc Nancy, Maurice Blanchot, or Giorgio Agamben frame it as «inoperative» (désoeuvrée), «disavowed» (désavouée), «unavowable» (inavouable), or «coming» (che viene) community,[2] as they mark its constant lingering on the borders, its evading features. Community appears as an ungraspable, fleeting moment which is never realised. The rifts in the structure where the inexistent comes into existence and the voiceless gains voice resides in a noplace/notime.

Therefore, it seems valid to ask how we can trace manifestations of communitas in art when it is not there or cannot even happen. André Lepecki strikes up a similar point with his remarks about the Rancièrian dissensus. The rift in the distribution of the sensible can remain a «disengaged» movement, a passive participation keeping the given structure in place.[3] Such is the problem of the ever-promised but never realised communitas – it frames a future, at the same time reiterating the structures of the now. Communitas understood this way could be seen as part of the «choreopolitical project underpinning contemporary control societies»[4], as he puts it starkly. The political on the other hand needs active engagement and a «movement that acts»[5], freeing itself from passively plodding along the given paths. According to Lepecki’s explanations on the example of dancers, a movement initiates the sphere of the political only when it opens a gap, an interval of unstructured, «unforeseeable»[6] space/time. The gap invites not to blindly follow the given move, but to initiate further steps, to enter interaction creatively. Thus, the dancers create an endless chain of, as Lepecki puts it, leadingfollowing or followingleading which is able to create ruptures, «fus[ing] and confus[ing] lines of authority and of submission»[7]. In these ephemeral, ever-moving openings initiated in artistic practice exist the possibilities of communitas, of non-hierarchical and «indifferent»[8], unpredictable and precarious bondings not based on identitarian in- and exclusions, but on the commonality resulting from interaction.

I would like to introduce yet another conceptual proposition, namely Roberto Esposito’s thoughts on communitas. Esposito, just like other deconstructionist thinkers, sees communitas as a fundamental openness of the being-together, as something which is in-between (an interval) and therefore both infinite and unstable, ecstatic and lacking at the same time.[9] What I find helpful is Esposito’s dismantling of communitas (and its counterpart immunitas) to its Latin core munus meaning «duty» or «function», hence referring to giving or doing something for others, to the exchange happening between the participants. So, we could speak of a givingtaking possible on all sorts of levels, from the exchange of material products and services to verbal and physical communication or affective engagement. Also, I think Esposito’s understanding of immunitas as counter movement to communitas helps to understand the mechanisms of disengagement, integrating a biopolitical perspective into his analyses.[10]

In now turning to consider the exhibition Producing Futures – An Exhibition on Post-Cyber-Feminisms (fig. 1), I would like to keep in mind the following questions: Can the exhibition «open the gap» and hence initiate «the unforeseeable»[11] of communitas and political change, or does it provoke political paralysis and disengagement by reconstructing hierarchies and creating dissensus in which we can passively partake?[12] How can we look for actualisations of communitas, and what/who would be its participants? Do we look at the exhibition as a whole and the participation of artists, art pieces, the architecture of the given building, curators, guides, leaflets, signs, and visitors as a conglomerate of munus? Or is the gap something which can occur in-between the observer and one of the artistic suggestions alone? In which way can we speak of a chain of movements, of an ongoing exchange or interaction?

Many of the mentioned questions cannot be answered by yes or no alone, if at all, as they are not exclusive but intermingling – while I might be affected of the exhibition as a whole experience, I might also relate specifically to one of the artistic suggestions, or I might be moved by the enthusiastic reception of my fellow visitors. Also, I do not believe we can give universal answers to the workings of communitas in this or any artistic context. This is why I will make observations on the exhibition drawing from my personal experience and interaction, hoping this will enlighten the way processes of communitas and immunitas may take place unpredictably but with certain backgrounds. Especially important in view of the given exhibition seems to me also to reconsider between what/whom interaction can take place, who/what can initiate communitas, or givingtaking? Cyber- and posthuman feminisms widen the understanding not only of communication, but also of subjectivities and (human) bodies, thus tracing mechanisms of immunitas in the way communitas is often conceptualised – a concept still discreetly lingering in the discursive field of white male academia. Three pieces by Anicka Yi – Home in 30 Days, Don‘t Wash, We Are Water, and Your Hand Feels like a Pillow that‘s Been Microwaved, all 2015 (fig. 2) – explicitly criticises «power structures of the art world and its institutional sexism»[13] as a form of immunisation against feminist movements or counter-networking, confronting it with a collective bacterial serum collected from 100 female artists. In doing so, Yi introduces the bacteria as some sort of agent developing and threatening to break down the immunitarian barriers of the art world on its own. However, these artistic suggestions develop their impact on the observer only when the context is explained, as the sculptures themselves remain in this respect mute – an observation I have made myself but also heard from other visitors. This reflects back on the question if our givingtaking is actually happening with the information sign or the guide telling us these details rather than with the artistic installations which leave us maybe bewildered, but not moved to act.

It is therefore important to remember that the visit of the exhibition is choreopolitically orchestrated and its experience mediated. Still we have many different possibilities to enter interaction or not, moving our bodies without having to submissively follow a certain track or being obliged to approach signs, for example. However, some movements are bound by spatial compulsions – to read an informatory sign, we do have to close in on a certain space on the wall, thus coming into interaction with other visitors blocking our view, stepping back and forward to let people pass or read etc. Here, we can almost speak of a dance, but maybe this is not exactly where the political suturing of followingleading is actualised.

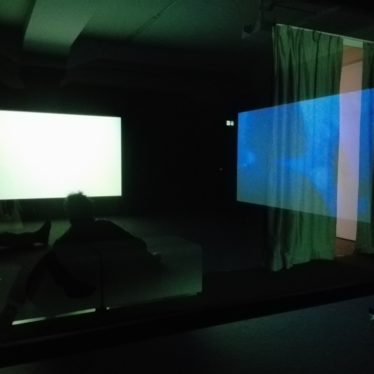

In Producing Futures, an interesting example for choreographic interaction with both the artistic suggestion and the fellow observers is the video installation A day in the life of bliss by Wu Tsang (2014). Arranged in a dark room, we find two screens with two different video projections, a mirror and a two-way mirror (fig. 3). Through the mirrors, the visitors sitting on beanbags are integrated into the piece, as they or parts of them are reflected; it becomes difficult to distinguish which movements happen solely on screen and which ones originate in the room itself. Moreover, in some of the video sequences we see yet another public watching the dance performance of a figure called BLIS. An impression of melting or interpenetrating realities arises, especially when the room is relatively crowded with visitors moving in and out frequently. Both Tsang and boychild, the performer impersonating BLIS, describe performance in the setting of nightlife as something which erases «boundaries in the dynamics of performer and viewer»: «You’re on the same level with the performance and the viewer; you’re on the floor together having the experience. […] It’s creating a shared space versus dominating.»[14] It is exactly this togetherness, which is initiated by the installation: in the dark, crowded room, you are unsure who is what; borders are shifting or getting obsolete, even when the performer is not bodily present.

The same artistic suggestion is worth considering also from a different choreographic perspective. Before entering the room, one may read the sign explaining some of the technical details of the production as well as the «idea» behind it or the interpretative suggestions the artistic installation offers. It may happen then that this information is «lost» the moment one steps into the room, both because visitors – I, at least – tend to superficially digest the information given on the signs or because the experienced artistic suggestion seems not to relate to the given information. In my perception, the information written on the sign – and later repeated by a guide – mainly told me about «online avatars, the so-called LOOKS [that] have developed consciousness. Parasites feeding on our vital energy, they have seized power and established a regime of pervasive control.»[15] However, I was so intrigued by the excitingly queer, non-binary corporeality of the protagonist(s) that this extra information left me rather bewildered. I tried to figure out where and how we would be able to «see» these LOOKS, unsure whether dancers would embody them, or how they related to the electronic gadgets the protagonists had and their eyes temporally turning blank (fig. 4). I couldn’t figure it out.

Nonetheless, I think exactly this edging uncertainty disallowed the complete immersion into the bodily movements of the protagonists, and to follow them passively. Their bodies were not just moving and looking in an unusual way, queering our everyday experience; they seemed to gain yet another uncanny layer because of the unfathomed connection to the (invisible?) LOOKS. This was turning the artistic suggestion even more exciting and attractive. I was strongly affected and moved from the reality of the exhibition into another sphere – also physically. I was somehow «feeling like you’re falling or being sucked into a vortex»[16], as Tsang describes the effect a music remix can have, comparing it to boychild’s performances. However, I would not say I was falling into a void, but into a commonality of bodies unbound, their layers both on screen and in the exhibition room developing something like a rhizome of movement and exchange, extending into an unknown virtual space, exploring forms of interaction with fellow bodies, immaterial entities and an obscure, fragmented physical environment. A day in the life of bliss was leading, I was following – maybe because I felt my understanding was somehow misfit with the direction proposed in the information sign. I engaged with the risk to stray from the path I felt was imposed upon me by the informative setting; I risked «activating movement towards the actualization of a yet unmapped nascent event»[17] and was therefore leading as I explored affectively something yet untold: the impression of a crowd, of the voluntary choreographisation of our bodies in material and virtual spaces. It was the impression of a common activation or active engagement. I would say this was the space/time we were actualising communitas, the moment of the political.

I suggest that the exhibition as a conglomerate of artistic works, their choreospatial arrangement, the supplementation by information signs or explanatory talks, and the actualisation by the observers can in certain space/times function as the interval of the political. But it can also – or in some parts – remain mute to us, it can bewilder us without opening a fissure, without allowing us to step in – an impression many observers shared when visiting the exhibition for the first time and without guide. The specific space/times when the exhibition is givingtaking and we are takinggiving, is very much dependent on our personal ability and will to process, (mis)understand and (mis)interpret the munus offered to us, on how our life stories, our personal experiences and convictions interact with the initiatives approaching us. We may stop dead in our tracks or we may engage in dance. I would therefore disagree with Lepecki as he describes leadingfollowing as an «a-personal singularity»[18]. I think to strip this «singularity» from its personal actualisation bears the danger of an universalisation feminist critique has taught us to be suspicious of. It happens all too fast, that certain «misfit», recalcitrant positions, certain experiences or identities are excluded. In the context of the exhibition Producing Futures, where these issues are topic and the artistic suggestions are part of a struggle for inclusion and empowerment of marginalised positions and for the transgression of the normative, it would be ignorant not to at least discuss this issue. The exhibition and the artistic suggestions choreographed within it strive to question and overcome partitions constructed as immunitarian boundaries – they perform in many ways a commonality embracing not only specifically gendered human beings, but extending to a post-human communication with material and virtual things, artificial intelligence and animals, celebrating «indifference».

Assuming that the space/time of the political can actually happen, I would like to pose one last question concerning the implications such an actualisation of communitas brings. When the fleeting moment of leadingfollowing passes – as the dancers stop to dance –, does it all fall to dust again? Or does it leave traces behind, a fissure like an ongoing tumult, still producing the future we have glimpsed during our interaction with the artistic suggestion? If we «understand the body as a reservoir of dissensual somatic-political capacities»[19], maybe it is possible to conserve something of the workings of the political, a lingering will to «misfit» without disengagement nesting in our bodies, nagging at our immunitarian boundaries.

The original version of this text was published in Senzacornice 20 / May-August 2019.

Pictures:

- Producing Futures – An Exhibition on Post-Cyber-Feminisms, upper floor, Migros Museum für Gegenwartskunst, Zurich, 2019

- Anicka Yi, Home in 30 Days, Don’t Wash, 2015

- and 4. Wu Tsang, A day in the life of bliss, 2014