The Zurich Museum Rietberg combines pleasant contrasts. Its exhibition space is spread over three historic 19th century villas and is complemented by an impressive new building called «Smaragd» (emerald), taking visitors several floors underground. It is in this setting that the country’s only museum devoted to traditional and contemporary art from Asia, Africa, the Americas and Oceania is housed. Its prestigious collection is impressive, comprising over 23’000 objects and even more ethnographic photographs.

If, however, the debates in recent years have proven anything, it is that separating art objects from their histories of origin has become almost impossible. The wealth that made these historic villas in the picturesque park in Zurich possible comes from trade relations that extend far beyond Switzerland’s borders. And yet the fiction of a European history that is not parasitically interwoven with non-European cultures persists.

So how does a Swiss museum that is explicitly dedicated to non-European art deal with this? As the current exhibition FIKTION KONGO at Rietberg shows: quite cleverly. The curators Michaela Oberhofer and Nanina Guyer juxtapose historical Congolese objects and photographs from German ethnologist Hans Himmelheber’s estate dating from the 1930s with positions of contemporary artists from the Democratic Republic of Congo and the diaspora. The result is a multifaceted exhibition that has been structured according to thematic focuses and makes the historical conditions under which some objects were produced comprehensible. Beyond that, not only will there be a collaboration with the University of Zurich to research the estate, but also to initiate an on-site discourse on colonial heritage. Nevertheless, FIKTION KONGO makes no secret of the fact that the findings that are revealed in the exhibition are also pure projections. Projections of both Western and African ideas, for the territory of the Democratic Republic of Congo is characterized by a diverse artistic production; and art and fiction draw equally from the imaginary.

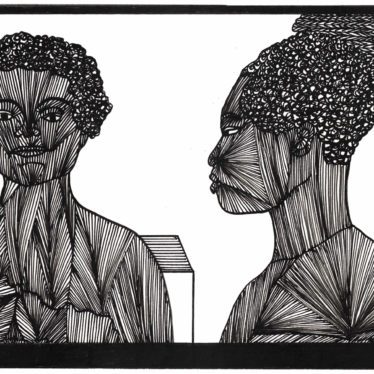

Instead of presenting a biased Western view of the objects in Himmelheber’s collection, the focus is on contemporary artists. The fact that this does not happen in the patronizing and equally misguided «we-give-marginalized-positions-a-voice» manner is already evident in the first room of the exhibition.

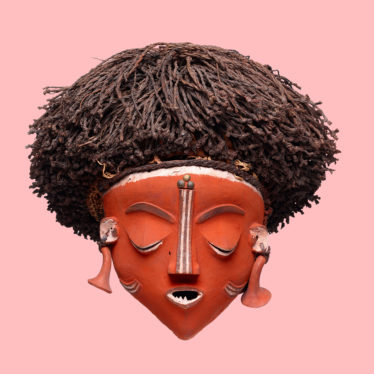

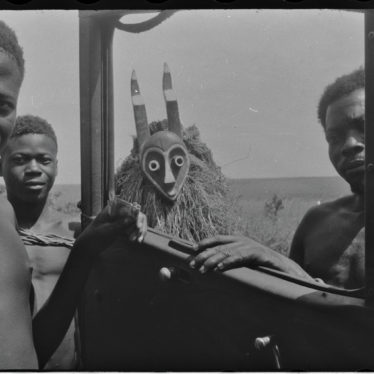

At the far end of the room a short video shows black-and-white photographs, while a voice-over reads diary entries. These are the thoughts of Hans Himmelheber, who first traveled to the Congo in 1938 and 1939. The objects from the collection that passed into the possession of the Rietberg Museum a few years ago – masks, fabrics and thousands of photographs – form the starting point of the exhibition.

On both sides of the room, however, there are also videos presenting the contemporary artists in the exhibition. While Himmelheber’s diary entries recount how he paid a ridiculously low price to be carried across the country in a sedan-like frame, the gazes of the fourteen artists are almost physically present. Thus the perspective changes, and the visitors of the exhibition become the ones viewed.

«There is no nonviolent way to look at somebody» an exhibition by Wu Tsang, theater director at the Zurich Schauspielhaus, recently proclaimed. But it is not the artists’ gazes that carry violence within them, it is the moment the perspective changes. While the colonial past is screened in the video with the photographs, the Congo’s present is watching. Effectively the first room of the exhibition already clearly shows that it is no longer possible to look at history in a vacuum.

Playful dialectics

Instead of losing themselves in a didactic approach of coming to terms with the past, the curators take on the content and meaning of the art objects with relish. The section «Design and Elegance», for example, presents art that takes a strongly visual approach. Various works of the Kuba people made of wood and shells are on display, but the focus is primarily on their textile art with its diverse abstract forms. A fabric measuring six meters in length, whose pattern is inspired by the tire prints of a motorcycle, shows the blending of tradition and newer influences. Yves Sambu’s photographs portray the fashion-conscious, extravagantly dressed sapeurs in Kinshasa. And the assertive attitude and class the fashion style is based on is the theme of the works of Fiona Bobo, who sought out sapeurs in Zurich.

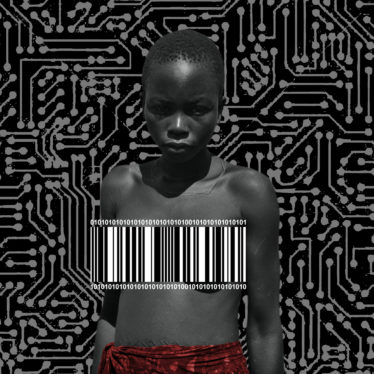

The connections between past and present are established in different ways: either formally, as in the section «Power and Politics», addressing the spiritual meaning of wooden power figurines, which are juxtaposed with a modern version of the wooden statue of Hilary Kuyangiko Balu. Or thematically, for example when Sammy Baloji x-rays and screens those very figurines, thus pointing to hidden objects that make up their ritual effect. Or directly, as in the installation by Michèle Magema, who by using some of the numerous ethnological photographs, symbolically «reclaims» the motifs on them by modifying them in her works and thus further developing their history.

Some of the artists have intensively engaged with ethnologist Himmelheber’s historical objects as part of a residency program, while other works were commissioned for the exhibition. Sinzo Aanza’s installation combines his poetic texts with sound recordings from the villages that Himmelheber visited, thus multiplying the route between Europe and Africa.

The section titled «Art Acquisition and Research» finally provides insights into the contexts in which Himmelheber’s objects were acquired, now enabling the visual indulgence in the impressive abundance of masks, figures, fabrics and craftsmanship in this Zurich museum.

The section «My Vision of Congo» features interviews with artists involved in the exhibition and other cultural producers, who talk about the historical moment we find ourselves in at this point in time. A moment that is marked by a close look at the fuzziness of history. Without a moralizing message, visitors are left with the feeling of not only wanting to finally take up this discourse properly, but needing to do so. Because it has been subject to one-sided fictions for far too long.

Thus, FIKTION KONGO shows an exhibition practice that promotes the non-European discourse within a European context. And even this only results in the creation of fictions, they do tap into the imaginary resources which new realities can ultimately emerge from. In art and beyond it.

Ann Mbuti is an art writer and cultural publicist based in Zurich, Switzerland. Her work connects the dots in the arts and culture that form a larger picture of the contemporary.

The text was first published at www.contemporaryand.com/fr/magazines/fiction-as-an-objective.